Dystopia 2042

Based on the prose of Ziemowit Szczerek.

[Polska wersja tutaj]

“There will always be someone who knows better than you what is good for you.” — Bertrand Russell.

Has anyone here ever been to North Korea?

I have.

It’s a bizarre fusion of an open-air museum and a concentration camp for minimalists.

Minimum food, minimum possessions, minimum knowledge, minimum freedom.

The daily routine? Worshiping the Beloved Leader by listening to endless loops about how miserable life is everywhere else, then toiling from dawn till dusk because the Beloved developed a whim to build a nuke and buy the latest Ferrari.

When Russia collapsed, they said Putin had turned it into a second North Korea.

But that’s a lie—Russia is far worse.

In North Korea, at least the streets are clean.

It is 2042, twelve years after the end of the eight-year war in Ukraine.

A war that was, supposedly, mere „self-defense”—a „special operation” slated for three weeks tops, marketed with the slogan: “Go on a short vacation, meet new people, and kill them.”

During this little „optional excursion” that overstayed its welcome, most healthy Russian men were minced by tanks into steak tartare à la Ukraine. Others were hunted down by drones linked to Tokyo gaming parlors in online war games. The rest were mangled by mines and shipped home as a „gift” to their families: “He was supposed to come back in one piece, but we’re returning one piece of him”—maybe it’ll fetch a price on the black market for organs.

Now, Russia is a land of the wrecked.

It’s dark comedy, really. The ones who returned were the career criminals, the clinical psychos, the addicts hooked on booze, spice, and slaughter—murderers rebranded as war heroes, draped in medals and „lifelong” respect.

Pity that „life” didn’t expire before they made it back.

They’re fit for nothing civil anymore, so crime is the only currency.

That’s the Russkiy Mir for you.

The „Security Services”—as the name implies—serve by ensuring this starving, downtrodden, and ravaged nation doesn’t raise its feeble, multi-million-strong hand against the very people to whom it owes this „paradise.”

“I don’t know if God exists, but if he does—he has a very specific sense of humor.” — Kurt Vonnegut.

Sure, I’m a calculating cynic. In my line of work, you have to be.

I no longer believe in good and evil—not after what I’ve seen.

If God exists, He must have had a hell of a hangover when He designed humanity.

After the fragmentation of Russia, I stood in Vladivostok, staring at the excavation for the Alaska tunnel Musk was supposed to build. A prime spot for smuggling nuclear warheads or… a submarine. Three thousand kilometers to the nearest hint of civilization; in the summer, it’s a swamp where mosquitoes carry off cows; in the winter… well, it’s cold.

I’ve seen Afghanistan, Beirut, Chechnya, Damascus… the Urals, Hungary, and Zabrze.

But I haven’t set foot in Matushka—the heart of Russia—in years.

Not in what’s left of her after successive regions, led by local warlords, tore themselves away.

They left just to return to a world where there are actually goods on the shelves, and you can walk to the store without worrying if Sniper Vanya had one too many and is using pedestrians for target practice. A world with uncensored internet, PornHub, and cinemas showing something other than Soviet-Russian „sublime” bile.

So yes, I’ve jumped into the deep end. I’m traveling through Belarus to Moscow—the capital of what remains of the „Great and Eternal Superpower.”

After the death of Batka Lukashenko, once the potato crops stabilized and the production of moonshine and cigarettes hit global standards, Belarus crawled back to Europe. Where it always belonged, anyway.

They built tracks… well, a single track, with a civilized European gauge. A reasonably fast train brought me comfortably to Minsk, where I had to switch to the broad-gauge rail—glacial and ancient—heading for Moscow.

At the border, the guard looked crumpled—either exhausted from pretending to be a Russian Ubermensch or poisoned by something he’d confiscated (rule number one: know what you’re stealing). He moved between compartments that reeked of the Soviet era: that unforgettable bouquet of cheap vodka, stale sweat, years of neglected cleaning, tobacco smoke, and „drop-through” latrines. He scrutinized my passport and visa with agonizing precision.

He found the „folded incentive” inside. He didn’t smile as he handed the documents back.

According to the Protocol of Conduct and Aesthetics of the Border Troops, he had to maintain a facade of majestic discipline.

Well, as is the country, so is the majesty.

Wretched Russia lost its luster after being hollowed out by the sanctions that rained down after the 2022 „self-defense” strike.

But in a totalitarian state, appearances are everything.

“Willkommen in Rossiya,” the soldier finally muttered.

“Thanks,” I replied, and he moved on to the next stage of his tedious, pointless ritual.

I get it—I could be taking something vital out, like a sack of onions or a radioactive brick. But what was he so afraid I was bringing in?

Probably just terrified he’d miss a piece of contraband that someone else could requisition later.

Relax, molodets, you won’t find what I’m carrying.

I adjusted my smart glasses. In a few minutes, they’d be dead weight.

AI, cloud uplink, AR overlays—all of it stops working a kilometer past the border.

Sanctions.

The Russian network runs on a proprietary, hermetic system, tightly leashed by the state.

At least the lenses are prescription—my eyes aren’t what they used to be.

“Welcome to the real world.” — Morpheus.

Naked reality was waiting. No filters. Raw, relentless, and drained of color.

“It’ll do you good,” laughed Svetlana, the woman in the next seat. She was heading home to share the pittance she’d earned cleaning floors in Minsk. “You’ll finally see what the real world looks like, sir.”

After two hours of idling in a field—a wait thick with nervous silence—the train finally lurched forward.

Russian territory greeted me with colossal flags. Faded, tattered, hanging limp from rusting masts.

A perfect monument to power.

The air was thick with women burdened by heavy bundles and men swearing at the world, bitterly comparing their lot to the „Western wealth” Belarus had recently tasted. This was another limb of the empire that was supposed to belong to the „All-Russian” dream, but had instead fled the decaying husk of the Motherland. Or maybe they just fled the Soviet Union 2.0 that Putin tried to resurrect.

“All because of that prick,” they whispered. “Good thing he finally kicked it.”

“Shame it was twenty years too late.”

Ironic, considering they were just recently putting up statues of Stalin. Human memory is a fragile thing.

Vladimir Putin didn’t end the world with a nuke. He didn’t take a bullet in a bunker. He wasn’t poisoned—though a few body doubles allegedly were. He didn’t even step down.

He just died. Of old age.

And by the time he did, Russia had already lost two decades to the void.

After hours of monotonous dozing, I finally hit Moscow.

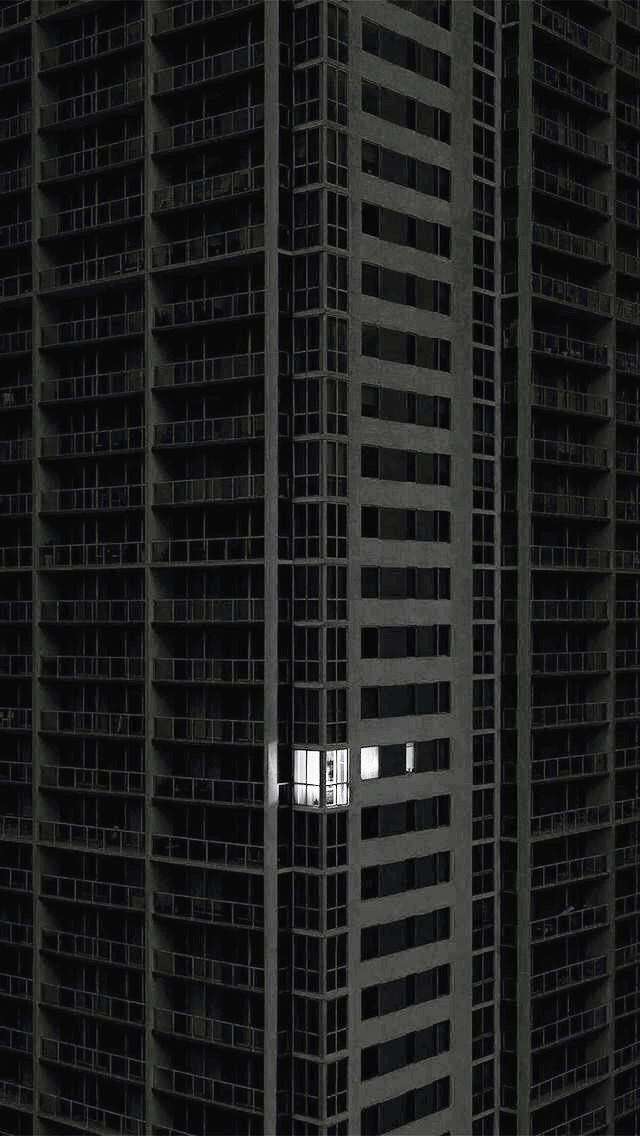

It was rich once—the ghosts of that wealth still haunt the skyline—but there’s little left. Unmaintained, unrenovated, and utterly bankrupt, the city is crumbling.

As the saying goes: you can’t cure syphilis with face powder.

There’s a protest on Red Square. Kids in Western rags screaming for the end of sanctions and for the government to „Recognize Reality.”

„Reality” is a loaded term here. Russia refuses to recognize the secession of its territories—from Crimea to Vladivostok. It refuses to acknowledge the new „Reality,” and the West refuses to lift the sanctions until it does.

“The Whole Nation Shall Rebuild Prosperity,” screams a slogan on a flickering, half-lit billboard.

The streets are choked with relics: Mercedes, BMWs, and Volkswagens from the early 2000s—back when machines were built to last. And Chinese EVs.

I looked for charging stations. The propaganda mills claimed Russia had invested heavily in green tech, but I didn’t see a single one.

Either it’s another state-sponsored lie, or people are charging those cheap Chinese buckets with extension cords dangled from high-rise windows.

Putin used to talk about „the ecology of electric vehicles.”

Not surprising—he had become a total vassal of Beijing. What else could he say?

“Russia embraces climate change with open arms.”

Well… maybe it’ll finally get warmer in this godforsaken place. Maybe something useful will actually grow in the north.

I doubt it. The permafrost will just vomit up ancient corpses, making things even more „jolly”… and hot.

“Use what talents you possess; the woods would be very silent if no birds sang there except those that sang best.” — Henry van Dyke.

It’s time to explain why I’m here.

It’s simple, really.

After years of total embargoes—sanctions on everything down to Spanish toilets—the gears finally ground to a halt. When the parts for cars, planes, and fridges evaporated, and the price of oil tanked so hard there weren’t enough petrorubels to fund the slaughter, people woke up.

When there was no one left to work because they were all being used as „cannon meat” at the front, and when Putin finally died, the realization hit: they were neck-deep in shit.

Eating lard and potatoes doesn’t pave the way to Greatness. Medals are hard to digest. You need hard currency.

So, any tourist insane enough to bring foreign cash and contraband goods was suddenly very welcome.

So here I am.

A tourist on the surface, but a smuggler at heart, hunting the score of a lifetime.

Does anyone know what a Quantum Crystal is?

Quantum memory.

Translucent-black with a faint shimmer, its internal layers flickering like stars in a miniature nebula. Manufactured by „ARX-K,” „MemNoir,” or the black-market „ChernStack.”

This tiny sliver of synthetic crystal—a centimeter long, weighing a few grams—is priceless. Its core is a labyrinth of engineered crystalline defects and carbon nanofibers. Inside, stable quantum states hold gargantuan amounts of data in the form of entangled qubits.

It is the only medium that can house thousands of terabytes in a tiny physical footprint, and it’s unreadable without the right „resonance key.” It’s immune to conventional data theft. It stores the truth: kompromat, banned art, evidence of war crimes, and fortunes in crypto.

On the black market, people don’t just pay for the memory; they pay for the power to restore a narrative—or destroy one.

A chronicle of war in a single crystal scroll—evidence that could shatter propaganda and fuel a tribunal.

A family heirloom around your neck that can buy your way past the FSB, bribe a gang, or keep you in pickled cucumbers and vodka for fifty years.

Theft, blackmail, chaos. Whatever you desire.

I’m carrying the high-end stuff: MemNoir. The luxury tier.

I’ve invested a lot of my own—and a lot of other people’s—money into this. People have died so that I can return with the crypto key stored on this sliver and live as a millionaire.

Finally, I’m in Moscow.

A „hard-currency guest,” which doesn’t mean I have a free pass.

I’m being watched.

I was taken to the Hotel Orbita.

It’s on the former New Arbat Avenue, now a graveyard of weeds and billboards that haven’t been changed in a decade. It used to be a four-star state flagship, boasting a rooftop restaurant and a lobby fountain.

The stars fell off the facade years ago. The fountain is a dry concrete husk.

The Orbita is where they still cage the Westerners.

It has electricity, tepid water, and a receptionist with a rehearsed, „hard-currency smile.”

The brochures still claim the „view of the Moskva River is breathtaking,” but all you see is a lot full of abandoned trolleybuses and a bazaar where babushkas sell rutabagas and jarred moonshine to survive another day.

The lobby is lit by dying fluorescents. Security cameras dangle from the ceiling like dead spiders, pretending they aren’t recording.

They are.

The walls are plastered with photos of „Old Moscow”: clean streets, neon ads, crowds with smartphones. Fiction for the gullible.

It feels quieter today.

Occasionally, a minibus of „tourists” from Berlin, Oslo, or Tokyo pulls up. A security officer disguised as a guide lectures them while they stare at the ruins like they’re visiting a museum of a failed civilization.

The rooms have wallpaper that predates the first sanctions and CRT TVs with three government channels.

But the sheets are clean, and for a bribe, the AC might actually kick in.

The bar serves „imported” beer that costs a fortune and tastes suspiciously like the local swill. A Russian cover of Hotel California drones from the speakers.

“Life consists of events that occur between what we know and what we learn too late to do anything about it.” — Taught by Mistakes.

The Orbita is the only safe harbor for a Zapadnik in this part of town. Safe enough to last the night, real enough to leave a scar.

Hustlers prowl the lobby. The FSB looks the other way—informal trade is the only way for the elite to get the luxury goods the sanctions took away.

“Phones, glasses, my friend?” they hiss. Then, lower: “Microchips?”

No, boys. I don’t deal in scrap. No chips for sale.

I have something else, but I’m not selling to some hotel-lobby tout. You couldn’t afford a single qubit.

I know exactly who will pay my price. Only a few people can get these crystals. Even fewer can smuggle them through the net.

I have my ways.

And I don’t even have to go looking for them. They’ll come to me.

I lie back on the bed, hands behind my head, legs crossed.

The wait begins.

The contractors will come to the room. They’ll take the crystal, they’ll transfer the crypto.

And I’ll be set for life.

The problem with the human race is that it regularly exceeds our darkest imaginings. We are vile, petty creatures, rutting in the mud we made, eyes fixed on a sky we’ve populated with ghosts just so we can sleep at night and dream up new excuses for our atrocities.

Yes. But with this money, I’ll buy my peace. I’ll buy redemption for every sin I’ve ever committed, right until the end of my days…

I jolted, pulled from my thoughts by the sharp trill of the hotel phone.

“Some gentlemen are here. They say ‚KGB’,” the receptionist said, her voice stiff with professional detachment.

I smiled, a wave of relief washing over me. Perfect.

„KGB”—the service abolished in 1991—was our pre-arranged code.

“Thank you. Send them up.”

I sat in the armchair and produced the quantum crystals.

A heavy knock at the door.

“Come in!”

Four men entered.

Two in long coats—the kind of fashion that went out with the Gestapo.

Two in fatigues, modern Kalashnikovs slung with practiced, lethal indifference.

I went cold.

“They brought us back into service last year, city boy. Didn’t you hear the news?”

I stared. It wasn’t a code.

They were the real KGB.

“Imagine you are dead. You have lived your life. Now, take what’s left and live it properly.” — Marcus Aurelius.

Dodaj komentarz